Hypertrophic scars and keloids are fibroproliferative disorders that result from aberrant wound healing in predisposed individuals following trauma, inflammation, surgery, or burns. ICD-10 code: L91.0

The formation of scar tissue is a physiological response to damage to the skin and mucous membranes. However, alterations in the metabolism of the extracellular matrix (imbalance between its degradation and synthesis) can lead to excessive scarring and the formation of keloids and hypertrophic scars.

The wound healing process, and thus the formation of scar tissue, involves three distinct stages: inflammation (within the first 48-72 hours after tissue damage), proliferation (up to 6 weeks), and remodeling or maturation (over 1 year or more). Prolonged or excessively pronounced inflammatory phases can contribute to increased scarring. According to recent research, in individuals with genetic predisposition, blood type A, skin phototypes IV-V-VI, scarring can develop due to various factors such as hyperimmunoglobulinemia IgE, hormonal changes (during puberty, pregnancy, etc.).

Abnormalities in fibroblasts and transforming growth factor-β1 play a key role in the formation of keloid scars. In addition, keloid scar tissue has an increased number of adipocytes associated with elevated levels of fibrosis promoters such as hypoxia-inducible factor-1α, vascular endothelial growth factor, and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1.

In the development of hypertrophic scars, the main role is attributed to the disruption of extracellular matrix metabolism in the newly synthesized connective tissue: hyperproduction and disturbance of intercellular matrix remodeling processes with increased expression of collagen types I and III. In addition, disturbances in the hemostasis system contribute to excessive neovascularization and prolong reepithelialization time.

Official data on the prevalence of keloids and hypertrophic scars are lacking. According to modern research, scarring is observed in 1.5-4.5% of individuals in the general population. Keloids are equally common in men and women and are more common in young people. There is a hereditary predisposition to the development of keloid scars: genetic studies suggest an autosomal dominant inheritance with incomplete penetrance.Normotrophic scars

Atrophic scars

Keloid scars

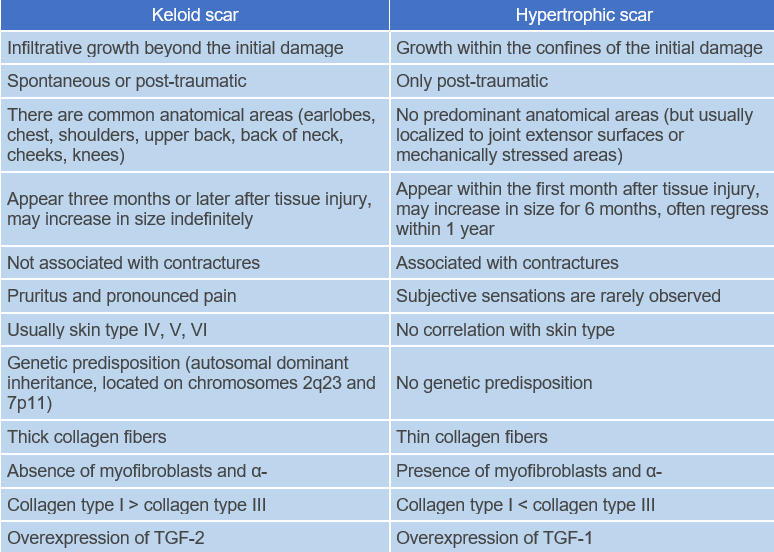

These are well-defined, dense nodules or plaques, ranging in color from pink to purple, with a smooth surface and uneven, fuzzy edges. Unlike hypertrophic scars, they are often associated with pain and hypersensitivity. The thin epidermis covering keloid scars is often eroded, and hyperpigmentation is common. Keloid scars form at least 3 months after tissue damage and may increase in size indefinitely.

As they grow, resembling pseudotumors with focal deformation, they extend beyond the boundaries of the original wound, they don't regress spontaneously and tend to recur after excision. The formation of keloid scars, including spontaneous ones, is observed in specific anatomical areas (earlobes, chest, shoulders, upper back, posterior neck, cheeks, knees).Hypertrophic scars

General remarks on therapy

Treatment goals:

- Stabilization of the pathological process.

- Achievement and maintenance of remission.

- Alleviation of subjective symptoms.

- Attainment of the desired cosmetic result.

Hypertrophic and keloid scars are benign skin conditions. The need for treatment is determined by the severity of subjective symptoms (e.g., itching/pain), functional impairment (e.g., contractures/mechanical irritation due to the height of the formations), and aesthetic factors that can significantly impact quality of life and lead to stigmatization.

None of the currently available scar therapies as monotherapy can achieve scar reduction or improvement of functional status and/or cosmetic appearance in all cases. In practice, a combination of treatment modalities is required in almost all clinical situations.

Requirements for treatment outcomes:

- Depending on the method of treatment, a positive clinical response (reduction of scar volume by 30-50%, reduction of subjective symptoms) can be achieved after 3-6 procedures or after 3-6 months of treatment.

- In case of unsatisfactory results after 3-6 procedures / 3-6 months, a modification of the therapy is necessary (combination with other methods / change of method / increase of dose).

Medication therapy

Intralesional injections:

- Triamcinolone acetonide 1 mg per 1 cm2 (not to exceed 30 mg per day in adults and 10 mg in children) intralesionally using a 30-gauge, 0.5-inch needle. Injections are given every 3-4 weeks. The total number of injections is individualized and depends on therapeutic response and potential side effects. Intralesional injection of triamcinolone acetonide after surgical excision of the scar prevents recurrence. or

- Betamethasone dipropionate (2 mg) + betamethasone sodium phosphate (5 mg) 0.2 mL per 1 cm2 intralesionally. The lesion is injected uniformly using a tuberculin syringe and a 25-gauge needle. The total amount of drug injected during 1 week should not exceed 1 ml.

- Intralesional injections of combination of methotrexate 1 ml and triamcinolone acetonide 0.5 ml and 1 ml 2% xylocain

- Intralesional 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) 40–50 mg/mL in combination with triamcinolone acetonide. Injections are given every 3-4 weeks.

Non-medication therapy

Cryosurgery:

Cryosurgery with liquid nitrogen results in complete or partial reduction of 60-75% of keloid scars after at least three sessions. The main side effects of cryosurgery are hypopigmentation, blistering, and delayed healing. The combination of cryosurgery with glucocorticoid injections has a synergistic effect due to more even distribution of the drug as a result of intercellular tissue edema after low-temperature exposure. Scars can be treated using the open cryospray method or the contact method with a cryoprobe. The duration of exposure is at least 30 seconds; the frequency of application is once every 3-4 weeks; the number of procedures is individual, but not less than 3.

Laser therapy:

Carbon Dioxide Laser. Treatment with CO2 laser can be performed in total or fractional mode. After total ablation of keloid scars with CO2 laser as a monotherapy, recurrence is observed in 90% of cases, so this type of treatment cannot be recommended as a monotherapy. The use of fractional laser modes allows to reduce the number of recurrences.

Pulsed dye laser. The pulsed dye laser (PDL) emits radiation at a wavelength of 585 nm, which corresponds to the peak absorption of hemoglobin in erythrocytes in blood vessels. In addition to direct vascular effects, PDL reduces transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) and the overexpression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) in keloid tissues. In most cases, the use of PDL has a positive effect on scar tissue in terms of softening, reduction in erythema intensity and reduction in elevation.

Surgical excision:

Surgical correction of scar changes is accompanied by recurrence in 50-100% of cases, except for keloids on the earlobes, which recur much less frequently. This situation is related to the specifics of the surgical technique, choice of method for closing the surgical defect, and various local tissue plastic surgery options.

Radiation therapy:

Radiation therapy is used as monotherapy or in addition to surgical excision. Surgical correction within 24 hours of radiotherapy is considered the most effective approach to treating keloid scars, significantly reducing the number of recurrences. The use of relatively high doses of radiation therapy during a short exposure time is recommended. Side effects of ionizing radiation include persistent erythema, skin peeling, telangiectasia, hypopigmentation, and the risk of carcinogenesis (there are several scientific reports of malignant transformation following radiation therapy of scars).

Prevention:

For individuals with a history of hypertrophic or keloid scarring, or who are about to undergo surgery in an area at high risk for their development, the following recommendations are advised:

For wounds at high risk of scarring, it is preferable to use silicone-based products. Silicone gel or sheets should be applied after the incision or wound has epithelialized and left in place for at least 1 month. It is recommended that silicone gel be used for at least 12 hours a day or, if possible, 24 hours a day with hygienic cleansing twice a day. The use of silicone gel may be preferred for extensive areas of involvement, for use on the face, and for individuals residing in hot and humid climates.

For patients with a moderate risk of scarring, silicone gel or sheets (preferably) hypoallergenic microporous tape may be used.

Patients with a low risk of scarring should be advised to follow standard hygiene procedures. If a patient is concerned about the possibility of scarring, silicone gel may be used.

An additional general precaution is to avoid sun exposure and use sunscreen with the highest sun protection factor (SPF > 50) until the scar matures.

Typically, the management approach for patients with scars can be reviewed 4-8 weeks after epithelialization to determine the need for additional scar correction procedures.